Lecture 7

Assignment 4 (Due 11/14 at 11:59pm)

Final Project (MS0 Due 11/21, MS1 Due 11/28, MS2 Due 12/5, MS3 Due 12/13 at 11:59pm)

Some Theory

Querying Methods for your React/Next.js App

| Promise-Based | Real-Time |

|---|---|

| If you need the data now, you can query for it | You already have the data |

| Data queries can be decentralized (done in any component) | Data queries are fetched and memoized through centralized (React) hooks |

| Quering data is imperative can quickly become spaghetti (and you lose some of the advantages of a declarative web UI framework) | Up-front cost to query data that pays off (because you don't Hopefully have to query it again) |

| There is no cleanup code | You first have to "subscribe" to changes in the data, then unsubscribe after you are done (kind of like opening and closing a file stream when reading a file) |

How do Callback/Promise-based vs. Real-Time Queries Look Like?

| Promise-Based | Real-Time |

|---|---|

| Single query, single async result | Single query, a stream of async results |

| - Async: result arrives at an unspecified time, outside the sequential execution context of the rest of your code | - ex: weather data |

| Run once, pass along indefinitely downstream (children & other descendants of your component) | Listenable data that needs to be "subscribed to" |

| Typically reacts to some update | Built on top of WebSockets |

| -ex: user click, first time a component loads, etc. | - ex: an abstraction over a byte stream |

| Good for… real-time applications |

How Do Callback/Promised Based vs. Real-Time Queries Work?

| Promise-Based | Real-Time |

|---|---|

| Typically calls a (backend) API route that fetches & returns data to you | Might call a backend route to pass data over a WebSocket |

| Usually built on top of HTTP requests | Or simply uses an API library to make calls directly to a database |

| Built on top pf HTTP Requests | - ex: Firebase Firestore call |

| Usually wrapped in a library like RxJS’s Observable data type or function calls that allow you to subscribe to changes | |

Choosing a Querying Method

As described in the first section, the type of queries your application will use will affect the app's architecture. In particular, real-time queries play nicely with having a centralized query that runs over a listenable data access object that is "owned" either by

- a top-level component (OK in small apps, but prone to prop drilling in more complex apps), or

- a custom React hook that wraps an effect (triggering an update when the data access object publishes a new version of the data)

That is not to say that your app cannot use both types of queries. It is just that a real-time application requires a specific architecture in which all data is queried first and passed along to components as props or referenced by components via (potentially custom) React/Redux hooks. This does not play nicely with callback/Promise-based queries because the data from the callback/Promise-based queries may be in an inconsistent state by the time the data from a real-time query has updated.

Your Firebase Firestore Application: Callback/Promise-based or Real-Time Queries

Firestore offers you a database that nicely organizes your data into documents and collections (groups of documents). It allows you to build queries that can either

- return once with a single snapshot of data (a Promise-based query), or

- allow you to hook into the data's live values (a real-time query).

Firestore Real-time Queries

Provides collection + document data as an listenable (subscribable) data object

- As soon as a collection updates, the collection access object publishes a new version of the collection

- As soon as a doc updates, the doc access object publishes a new version of the doc This can be passed as a React prop or an effect dependency, which triggers a component update!

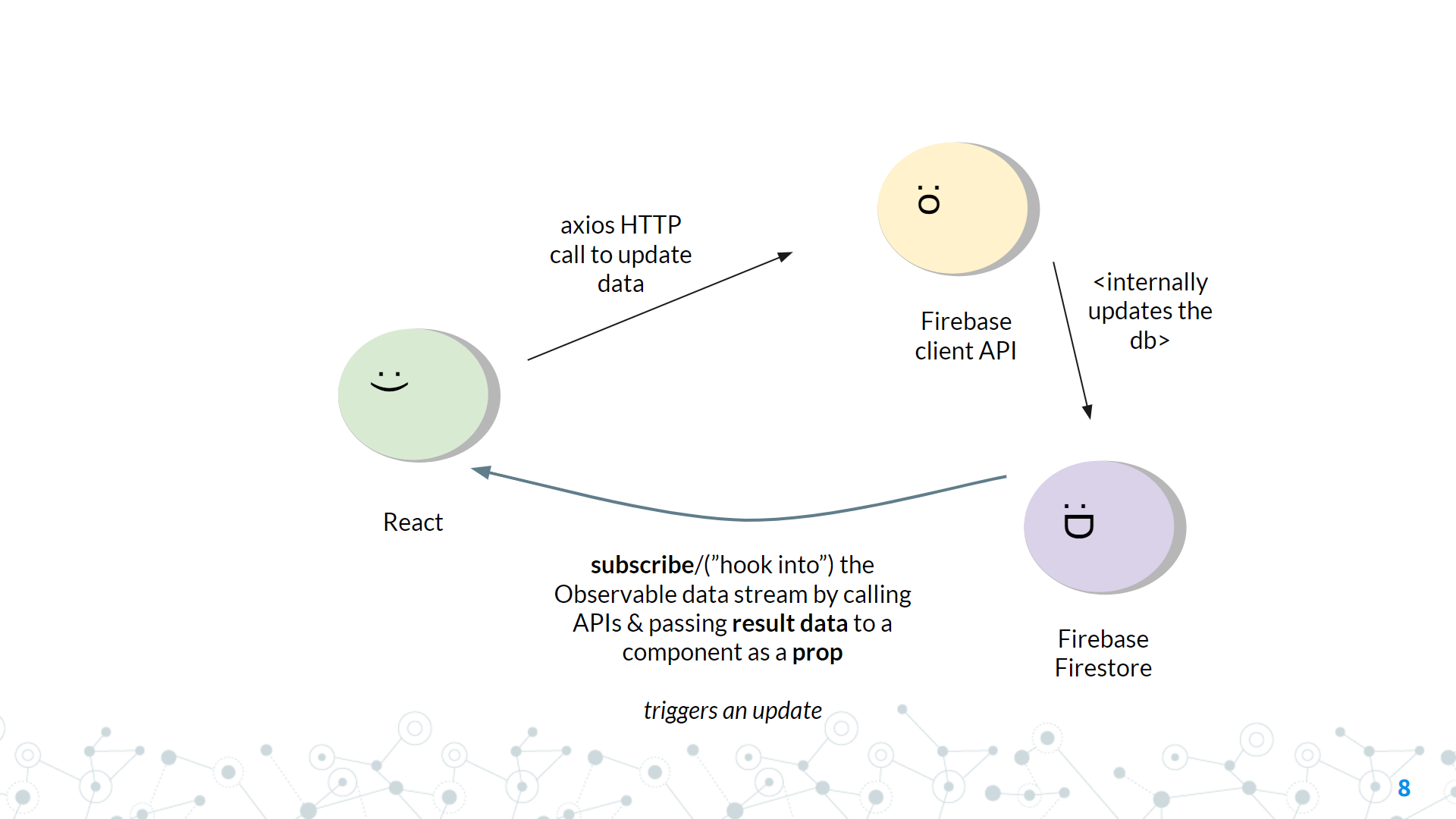

Anatomy of a Firebase Firestore Real-Time Application (The "Full" Stack)

Unlike callback/promise-based queries, the connection between updating and fetching data is completely gone. Updating data occurs along an entirely separate channel from subscribing to the data. This means that implementing calls to update data will look very different

Miscellaneous Advice

When designing a system:

- avoid two-way dependencies (or as many dependencies as possible)

- as with React & declarative web frameworks, one-way data binding is the way to go

- avoids: more things to update

- avoids: more surface area for synchronization errors

This philosophy helps us prefer real-time queries over Promise-based queries, because there is only a single dependency for the queried data, rather than the set of all the decentralized Promise-based queries.

The Practice

The Problem

Suppose you want to create a book rating platform 📚! Users will be able to search a book by title or author and see its avg. rating.

Users will be able to submit book reviews 📩 (one per book title max!) for a given title + author with a rating of 1-5 stars.

A review on a new book will upsert the set of books with a new book (if necessary) and a review associated with that book.

What can the user see?

- Reviews

- by book title

- by author

- by reviewer

- sort by avg. rating

Modeling the Problem

Q: What are the main entities in the model?

AKA, what moving parts contribute to the changing data in the system?

- books (have authors & get reviewed)

- users (user === reviewer)

- book reviews (for a book, by a user)

- author (books may have the same title but different authors)

Q: If each Entity can be represented by a data object, what will the structure be like?

Book

- title (string)

- author (string)

Review

- rating (number 1-5)

- description (string)

- title (string)

- author (string)

Reviewer/User

- email (string)

Author

Authors are not a primary entity. The author is a very simple object that does not "own" any other data, at least according to the specifications of our book reviews platform. We may need to fetch books by author, but we do not ever need to know the list of all authors, for example.

Building Out our Solution

Q: What Typescript types do we need to write make our data structures concrete?

Aside: Types or Interfaces?

| Type | Interface |

|---|---|

| Better suited for raw data | Useful for a communication protocol or for rich objects with behavior (methods) |

| (typically) has no functionality | Implemented by a class, which handles methods (class functions) efficiently |

| Supports declaring methods, but this can only be implemented less efficiently | Usually wrapped in a library like RxJS’s Observable data type |

So What will our database type schema look like?

A no-brainer! Just take the above and shove them into a TypeScript file (types/index.ts):

export type FireBook = {

title: string;

author: string;

};

export type FireReview = {

rating: number;

title: string;

author: string;

reviewer: string;

};

export type FireReviewer = {

email: string;

};

Note that the primary reason we create a FireReviewer (user) for the site is to make authentication easiser. Firebase has nice features that can allow easy sign-on with Google OAuth and can pass along the signed in user's uid and email for us to store into Firestore into a reviewers collection. Nice.

Upgrading our Types

There is a slight problem: the types shown above are perfect for enforcing/describing the data going into Book, Review, and Reviewer documents. But they are not enough to address a specific document! In order to address a specific document, it is necessary to create track an ID.

What we can do is the following: create an new FireDocument type and declare new types for Book, Review, and Reviewer as an intersection of FireXX and FireDocument!

export type FireDoc = {

id: string;

};

export type Book = FireDoc & FireBook;

export type Review = FireDoc & FireReview;

export type Reviewer = FireDoc & FireReviewer;

Great! Now we can address specific documents. In this case, the uid of a logged-in user will serve as the id of the user's own document. Now given a full Review type, for example, it is possible for Firestore to retreive the exact Review that we need.

Setting Up our Database

Create Collections

In order to track our Books, Reviews, and users (reviewers), we need to create collections for them each. Let's call them books, reviewers, and reviews.

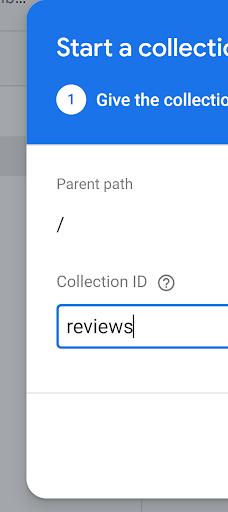

Let's start a collection!

Now let's give it a name!

(Now repeat this for the other two collections)

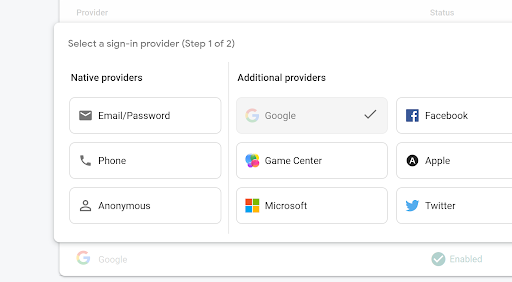

Set Up Authentication

As mentioned above, Firebase has nice integration with Google sign-on. Let's take advantage of this!

Open the Authentication Tab...

...and select the 'Google' authentication strategy (this uses the Google sign-on)

And on the client-side:

// TODO: Replace with your own Firebase config

const firebaseConfig = {

apiKey: 'asfasdfasdf',

authDomain: 'trends-sp22-lecture-8.firebaseapp.com',

projectId: 'trends-sp22-lecture-8',

storageBucket: 'trends-sp22-lecture-8.appspot.com',

messagingSenderId: 'sijiofdsjdi',

appId: '1:3209483200:web:u897j8ydq973342',

};

const app = getApps().length ? getApp() : initializeApp(firebaseConfig);

const db = getFirestore(app);

const provider = new GoogleAuthProvider();

provider.setCustomParameters({

login_hint: 'user@example.com',

hd: 'cornell.edu',

});

provider.addScope('email');

const auth = getAuth();

signInWithPopup(auth, provider)

.then((result) => {

// This gives you a Google Access Token. You can use it to access the Google API.

const credential = GoogleAuthProvider.credentialFromResult(result);

const token = credential?.accessToken;

// The signed-in user info.

const user = result.user;

userUpload(user, db);

// ...

})

.catch((error) => {

// Handle Errors here.

const errorCode = error.code;

const errorMessage = error.message;

// The email of the user's account used.

const email = error.email;

// The AuthCredential type that was used.

const credential = GoogleAuthProvider.credentialFromError(error);

// ...

});

export { db };

Architecting the App

Avoid Hard-coding Routes!

It's a good practice to avoid hard-coding constants such as the path to each collection. Better to include these into a fireRoutes.ts file:

export const BOOKS_PATH = 'books';

export const REVIEWERS_PATH = 'reviewers';

export const REVIEWS_PATH = 'reviews';

Writing our collection query hooks

With the database set up, we need to build queries on the database as well as actions that can write to the database. To avoid prop drilling, we need to build custom React hooks that allow any component to use and "hook into" our data. Our custom hooks need to always have the most up-to-date data available (it is a real-time database after all), so we need to store the information in state variables (so that any components using these variables will be updated when the variable updates).

We can start this a file fireHooks.ts:

const useCollectionWithCallback = (

collectionId: string,

callback: () => void,

) => {

const [coll, setColl] = useState<DocumentData[] | undefined>();

const collectionRef = collection(db, collectionId);

// Trigger an effect whenever the query returns a new snapshot

useEffect(() => {

const unsubscribe = onSnapshot(query(collectionRef), (querySnapshot) => {

const docsInCollection: DocumentData[] = [];

querySnapshot.forEach((doc) => docsInCollection.push(doc.data()));

// in the effect, set the collection data. This triggers an update in any component using 'coll' (using this collection hook).

setColl(docsInCollection);

callback();

});

return () => {

// run any any cleanup code

unsubscribe();

};

}, [collectionId]);

return coll;

};

Alternatively, in a slightly nicer (more functional, more Observable-y way), we can use the rxFire package to simplify some of the code for us:

const useCollectionWithCallback2 = (

collectionId: string,

callback: () => void,

) => {

const [coll, setColl] = useState<DocumentData[] | undefined>();

const collectionRef = collection(db, collectionId);

// trigger an effect whenever the collectionData observable publishes a new version of the data

useEffect(() => {

const subscription = collectionData(collectionRef).subscribe(

(c: DocumentData[]) => {

// in the effect, set the collection data. This triggers an update in any component using 'coll' (using this collection hook).

setColl(c);

callback();

},

);

return () => {

// run any any cleanup code

subscription.unsubscribe();

};

}, [collectionId]);

return coll;

};

Build Actions to Write to our Database

Recall the 'anatomy of a Firestore real-time app' image. Now that we have hooked into our data, we need calls that will write to the data. In our case, we need calls to add, edit, and delete reviews. We also need calls to add books and get books/reviews by ID. NOTE: in this tutorial, we use the shortcut of concatenating titles and authors/reviewers to generate document IDs. DO NOT ACTUALLY DO THIS! Do the extra work of generating a Firestore document id with doc().

Editing reviews:

export const editReview = async (id: string, update: Partial<FireReview>) => {

await setDoc(doc(db, REVIEWS_PATH, id), update, { merge: true });

};

Adding reviews:

export const addReview = async (id: string, book: FireReview) => {

// shh

editReview(id, book);

};

Deleting reviews.

export const deleteReview = async (id: string) => {

await deleteDoc(doc(db, REVIEWS_PATH, id));

};

Adding a book (when there is a new revew on a book that does not quite exist). Note that we use a transaction to create the book, because multiple users can attempt to create a book at the same time, so there may be data races (and we want to avoid duplicate entries).

export const addBook = async (id: string, book: FireBook) => {

try {

await runTransaction(db, async (transaction) => {

const bookDocRef = doc(db, BOOKS_PATH, id);

const bookDoc = await transaction.get(bookDocRef);

if (bookDoc.exists()) {

throw `Book ${book.title} by ${book.author} already exists!`;

}

transaction.update(bookDocRef, book);

});

} catch (e) {

console.log('Transaction failed: ', e);

}

};

Getting books and reviews by id:

export const getBookId = (book: FireBook) => {

return `${book.title}::${book.author}`;

};

export const getReviewId = (review: FireReview) => {

return `${review.title}::${review.author}::${review.reviewer}`;

};

Uploading a user when auth:

export const userUpload = (user: User | null, db: Firestore) => {

if (user != null) {

const uid = user.uid;

const email = user.email || 'Dummy Email';

runTransaction(db, async (transaction) => {

const userDocumentReference = doc(collection(db, REVIEWERS_PATH), uid);

const userDocument = await transaction.get(userDocumentReference);

if (!userDocument.exists()) {

const fullUserDocument: FireReviewer = {

email,

};

transaction.set(userDocumentReference, fullUserDocument);

}

// eslint-disable-next-line no-console

}).catch(() => console.error('Unable to upload user.'));

}

};

Finally, the filters to search & sort reviews

import { FireReview } from '../types';

export const sortByRating = (reviews: FireReview[]) =>

[...reviews].sort((reviewA, reviewB) => reviewA.rating - reviewB.rating);

export const filterByTitle = (reviews: FireReview[], title: string) =>

reviews.filter((review) => review.title === title);

export const filterByAuthor = (reviews: FireReview[], author: string) =>

reviews.filter((review) => review.author === author);

export const filterByReviewer = (reviews: FireReview[], reviewer: string) =>

reviews.filter((review) => review.reviewer === reviewer);

export const filterByBook = (

reviews: FireReview[],

title: string,

author: string,

) =>

reviews.filter(

(review) => review.title === title && review.author === author,

);

Now how can we use the above functions to implement the main feature of our books review platform?

export const getAvgRatingForBook = (

reviews: FireReview[],

title: string,

author: string,

) => {

const filteredList = filterByBook(reviews, title, author);

return (

filteredList.reduce((prevSum, review) => prevSum + review.rating, 0) /

filteredList.length

);

};

export const paginateReviews = (

reviews: FireReview[],

resultsPerPage: number,

page: number,

) => {

const lastPage = Math.ceil((reviews.length + 1) / page);

const pageSanitized = Math.min(Math.max(0, page), lastPage);

return reviews.filter(

(value, i) =>

i > pageSanitized * resultsPerPage &&

i < Math.min(pageSanitized + 1, lastPage),

);

};